The first open heart operation was performed; the procedure would soon be dramatically improved by a new heart-lung machine. Other surgical firsts: a repair of a blocked carotid artery and a successful transplant of a human organ (kidney).

1950

First African-American Woman Admitted to College

1950

First African-American Woman Admitted to College

A specialist in obstetrics and gynecology, Helen O. Dickens, MD, FACS, was the first African-American woman admitted as a Fellow of the College. Born in Dayton, OH, Dr. Dickens was the daughter of a former slave who changed his last name to Dickens after meeting Charles Dickens, the great 19th Century novelist.88 Dr. Dickens gained recognition in the medical profession and education community for her research into teen pregnancy and sexual health issues. Her research helped equip schools, parents, and health professionals with intervention strategies to decrease teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.89

Citations

1952

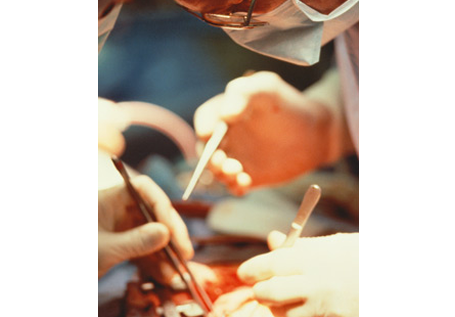

First Open Heart Operation Performed

1952

First Open Heart Operation Performed

University of Minnesota surgeons, led by F. John Lewis, MD, performed the first open heart surgery on a five-year-old girl who had been born with a hole in her heart. The patient's body temperature was reduced by immersion into a tub of ice water contained in a watering tank designed for a horse farm so she could survive longer without a pumping heart.90 Clamping the inflow to her heart so that it emptied of blood, Dr. Lewis, assisted by C. Walton Lillehei, MD, PhD, FACS, cut open her still beating heart and quickly sewed up the hole. With the repaired heart working properly for the first time in her life, the girl was then immersed in a bath of warm water to bring her body temperature back to normal. The operation was a success.91

Citations

1952

Joint Commission Takes Over the College's Role in Providing Voluntary Hospital Accreditation

1952

Joint Commission Takes Over the College's Role in Providing Voluntary Hospital Accreditation

When Major General Paul R. Hawley, MD, FACS (Hon),92 took over as Director of the College in 1951, he quickly realized that the Hospital Standardization Program had become a serious financial drain that the College could no longer afford.93 When the College discussed having the program taken over by the American Hospital Association (AHA), however, the American Medical Association (AMA) strongly objected that the arrangement would compromise both the autonomy of physicians and the doctor-patient relationship.94 Other alternatives were discussed, but each had its issues, prompting Dr. Hawley to say, "I agree with everything that has been said, but we are broke."95 Finally, Evarts A. Graham, MD, FACS, proposed creating an independent "joint commission" to take over the primary task of providing voluntary hospital accreditation.96 The College joined with the AHA, AMA, the American College of Physicians, and the Canadian Medical Association to create the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals (recently shortened to "The Joint Commission"), and appointed the members of its governing body, the Board of Commissioners.97

Citations

1952

College Launches Public Campaign Against Fee-Splitting

1952

College Launches Public Campaign Against Fee-Splitting

When Evarts A. Graham, MD, FACS, once the College's most severe critic, was elected chairman of the Board of Regents, he immediately set out to put an end to fee-splitting. In his first speech to the College's Regents, Dr. Graham said: "We have good hospitals, and we have good young surgeons who can't get the surgery to do, because everywhere they go they are confronted with the horrible odor of fee-splitting … I think that the College ought to undertake a vigorous offensive campaign against fee-splitting and not be content with signing pledges."98 The College held a press conference during Clinical Congress where College Director Paul Hawley, MD, FACS (Hon) and the Regents publicly explained how the practice of fee-splitting (doctors getting paid to refer patients to other doctors) and its variations were "dishonest and unethical."99 A few months later, in an interview with U.S. News and World Report, Dr. Hawley said fee-splitting sometimes led to unnecessary surgery. There was a vehement reaction, and not just from the fee-splitters. Believing the College had publicly impugned the reputation of the entire profession, hundreds of anti-fee-splitting doctors demanded that the College fire Dr. Hawley. But the College and its leaders weathered the storm and reform occurred. Public awareness of the issue made many doctors cautious about violating the College's principles; the Joint Commission required hospitals to have methods to prevent fee-splitting in place; and groups of surgeons in communities pledged not to split fees. Within two decades, fee-splitting was no longer an issue.

Citations

1953

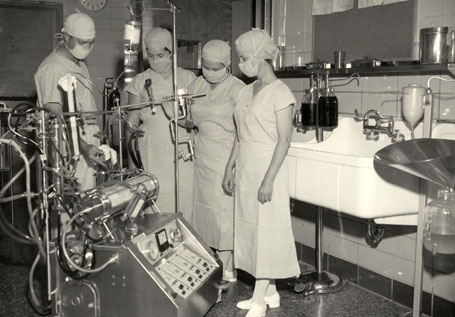

"Heart-Lung Machine" Used to Perform Open Heart Surgery

1953

"Heart-Lung Machine" Used to Perform Open Heart Surgery

In 1931, John H. Gibbon, Jr., MD, FACS, had an inspiration while he watched a patient die from pulmonary embolectomy. "During that long night, helplessly watching the patient struggle for life as her blood became darker and her veins more distended, the idea naturally occurred to me that if it were possible to remove continuously some of the blue blood from the patient's swollen veins, put oxygen into that blood and allow carbon dioxide to escape from it, and then to inject continuously the now-red blood back into the patient's arteries, we might have saved her life," he said.100 Collaborating with his wife Mary, Dr. Gibbon worked to develop an extracorporeal circulatory device or "heart-lung machine." By 1942, he was able to keep cats alive on his experimental devices even after bypass. In 1950, he received support from International Business Machines Corp. (IBM) to build a heart-lung machine on a more sophisticated scale. Finally, on May 6, 1953, Dr. Gibbon used the device to provide a patient with continuous blood flow during an open heart procedure to close a hole between the upper chambers of the heart of an 18-year-old woman.101 The procedure's success would dramatically change the field of cardiac surgery and the approach to the treatment of cardiac disease.102

Citations

1954

First Successful Human Organ Transplant Procedure Performed

1954

First Successful Human Organ Transplant Procedure Performed

With identical twin brothers, Ronald and Richard Herrick, serving as donor and recipient, Joseph E. Murray, MD, FACS, performed the first successful human organ transplant—a kidney—at Boston's Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. Dr. Murray recounted that "although I was well aware of the time ticking away throughout the procedure—everyone was—I could only continue to work carefully and systematically and, at all costs, efficiently. We would know soon enough whether I had succeeded. There was a collective hush in the operating room as we gently removed the clamps from the vessels newly attached to the donor kidney. As blood flow was restored, Richard's new kidney began to become engorged and turn pink... There were grins all around."103,104 Identical twins were used to eliminate any problems of an immune reaction. In 1990, in recognition of the first successful human organ transplant and other medical accomplishments, Dr. Murray received the Nobel Prize for Medicine.105

Citations

1954

First Carotid Artery Surgery Successfully Performed and Published

1954

First Carotid Artery Surgery Successfully Performed and Published

Prof. George Pickering (St. Mary's Hospital, London) examined a 66-year-old woman with intermittent paralysis on her right side and blindness in her left eye. Ordering a carotid arteriogram, he found she had a significant lesion in her left carotid artery. Prof. Pickering suggested to his surgery professor colleague, Charles Rob, MD, FACS,106 that the blockage might be corrected by surgery—a suggestion based on the theory that carotid disease is localized and could conceivably be bypassed or locally excised. Dr. Rob's assistant director, Felix Eastcott, MD, FACS (Hon) performed the operation under Dr. Rob's supervision, in which the localized lesion was removed and the carotid was reconstructed. The case was a success (in fact, the patient's symptoms were completely relieved and she lived for nearly 20 more years), and it was published in the Lancet. Although others claimed to have previously performed the procedure, their cases had not been published in a scientific journal. Despite the international prominence of the Lancet and of Dr. Rob, the operation's acceptance by the neurological community was slow and awaited controlled clinical trials.107 Nevertheless, the case led to carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting assuming prominent roles in the prevention of stroke.108

Citations

1959

Endoscopy Vastly Improved Through Application of Hopkins Rod-Lens System

1959

Endoscopy Vastly Improved Through Application of Hopkins Rod-Lens System

Hungarian surgeon George Berci, MD, FACS,109 had long been vexed by a major problem in gallbladder procedures—surgeons could not see inside the common bile duct well enough to remove gallstones. "The stones were overlooked, and approximately 12 percent of patients had to undergo another procedure to remove them," he said. "I thought it would be nice to insert something in the duct that would let you remove the stones under visual control."110 Dr. Berci sought help from Prof. Harold Hopkins, a renowned physicist and professor of applied optics in London. Dr. Berci became actively involved in launching the clinical application of the Hopkins rod-lens system into endoscopy, vastly improving the visual field for this procedure.111 The new device was the beginning of a transformation of the quality of endoscopic instrumentation for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in many specialties, and this development, in turn, revolutionized the field of surgical specialties so that minimal access surgery is now commonplace for many specialty procedures.

Citations

1959

College Sponsors New Group to Develop Cancer Staging System

1959

College Sponsors New Group to Develop Cancer Staging System

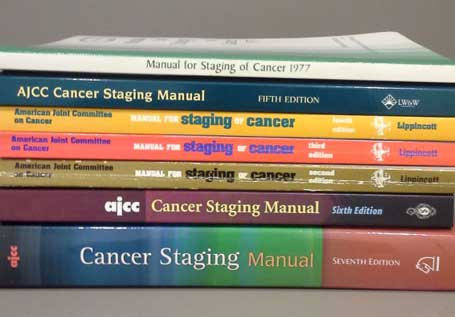

The American Joint Committee on Cancer was organized to develop a cancer staging system acceptable to, and used by, the American medical profession for selecting the most effective treatment, determining prognosis, and continuing evaluation of cancer control measures. The College was one of six administrative sponsors, with the others being the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, and the College of American Pathologists. The committee also was dedicated to educating the oncology community, supporting research and developing tools to classify and predict cancer, foster collaborative efforts and support efforts to improve care and predict outcomes for cancer patients.112

Citations